Eradicating life-threatening diseases by improving vaccination rates is a difficult, complex and time-consuming process. However, safety scares can emerge rapidly, go “viral”, and cause a sudden drop in vaccination rates.

Social media can play a role in either reducing – or increasing – public anxiety around safety scares. Therefore, Public health officials need to be prepared to respond rapidly to avoid public hesitancy. Education for public health workers and access to vaccines also need to be improved.

These are some of the key conclusions from panelists at Cambre’s policy discussion Vaccines, “Fake News” and the European Elections, which took place on 25 April at the Brussels Press Club. Moderated by Eva Bille, of Cambre’s Healthcare Team, the panel included senior experts from the EU Institutions, academia, industry, technology platforms and traditional media.

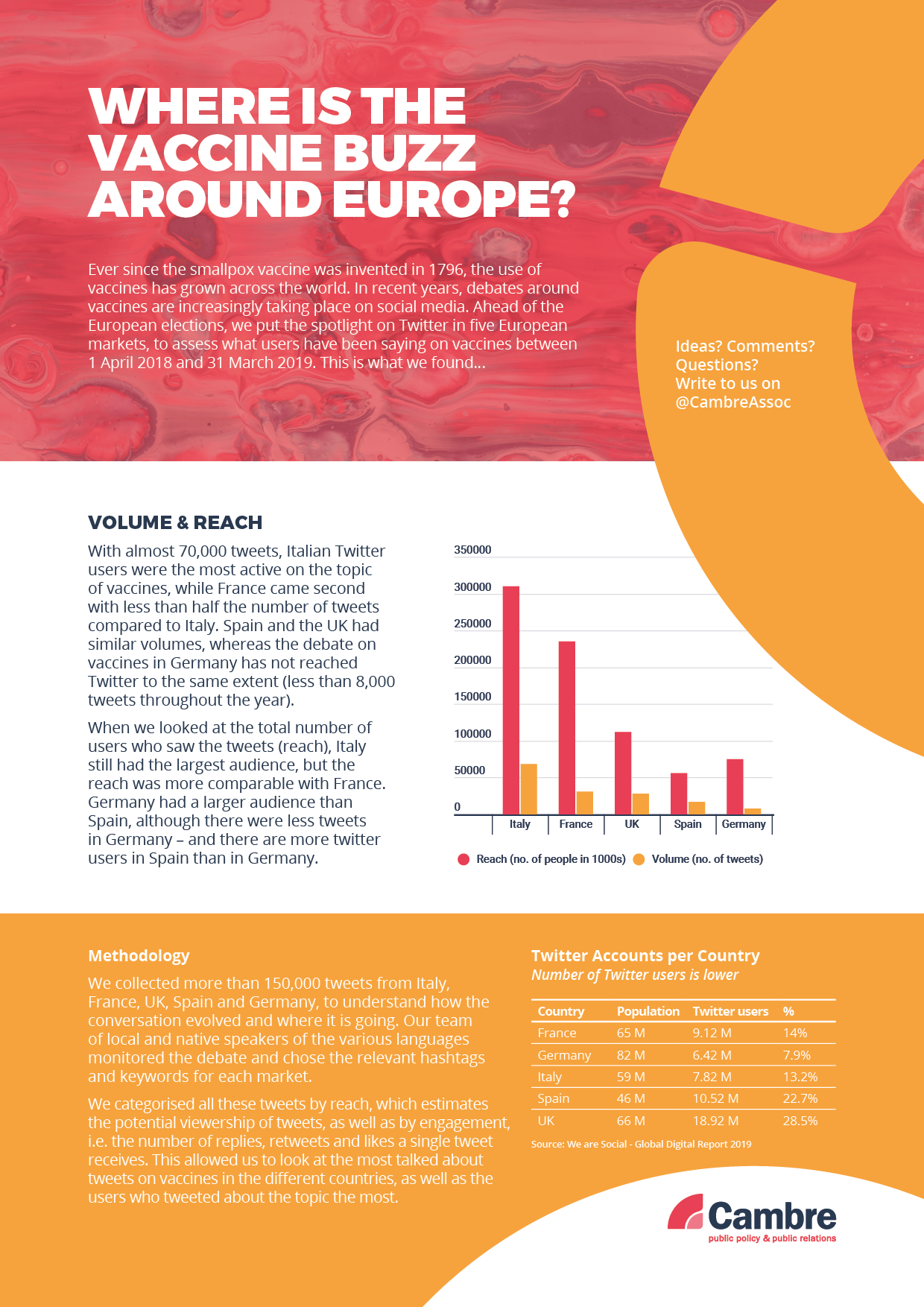

Eva opened the discussion by presenting an analysis of over 150,000 Tweets relating to vaccines over the past 12 months collected by Cambre from Italy, France, UK, Spain and Germany. Italy saw the largest number of Tweets and also the largest “reach” of the conversations on vaccines (number of people who saw them). National political figures were very prominent in the Italian discussions – former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and leader of the Italian Democratic Party, Caterina Coppola reached mass audiences with Tweets supportive of vaccination. In France Marine Le Pen of France’s hard-right National Rally linked the vaccination debate to immigration in line with her political leanings.

All panel members emphasised that what people see on social (and traditional) media is just one among many factors in their decisions on whether to vaccinate or not. Isabel de la Mata, Principal Advisor on Health in DG SANTE, European Commission mentioned the key importance of advice given by doctors and other health professionals. They remain by far the most trusted source of health information among Europeans. That is why the Commission this year fostered the creation of a Coalition for Vaccination with EU-level associations representing health workers.

Ciara O’Rourke, Director of Global Public Policy – Vaccine Confidence, MSD and Robb Butler of UNICEF emphasised the importance of health services that make it easy for busy people, such as parents of young children, to access vaccination. Ciara also pointed out that health systems need to aim for a resilient pro-vaccination eco-system, rather than just passive support among patients and health workers. This is what has been fostered in Denmark and Ireland. Both were hit with social media-driven scare stories about the safety of the HPV vaccine. Yet both managed to rapidly contain the scares and build vaccine acceptance rates back up within a few years.

Although it is not the only factor, both Emilie Karafillakis, Research Fellow & PhD Candidate, London School of Science and Tropical Medicine and Raegan Macdonald, Head of Public Policy, Mozilla said social media has fundamentally changed the relationship between health workers and patients. Many Europeans now go to see their doctor empowered with information they have found on social media. That information can be of variable quality. Raegan pointed out that social media algorithms currently prioritise viewer engagement, rather than accuracy of information. This means that sensationalistic mis-information or “fake news” is often given more prominence than scientifically accurate (but unexciting) information. Indeed, highly sensational mis-information is sometimes so engaging that it goes viral – achieving huge prominence. Emilie pointed out that parents making decisions about whether to vaccinate their children have always worried. What is new with social media is that they can now share their concerns with a wide audience. Some social media users exploit this concern as a way of boosting their profile. Emilie identified three groups that are particularly liable to do this: celebrities without any medical training; celebrity “health experts” who may or may not have medical training (and who are often promoting a book, a video or a “wellness product”); and politicians – particularly those that position themselves as being against “the elite” and against “experts”.

Kate Kelland, Health and Science Correspondent for Europe Middle East and Africa, Reuters recalled her experience of working as a political correspondent for Reuters in the UK in the 1990s when there was a scare story (based on bad science) about the safety of the MMR vaccine. At a news briefing by the spokesman of the then British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, the political correspondents spent all their time asking about whether Mr. Blair’s infant son had received the MMR vaccine. She also recalls editors insisting on balance – resulting in “fake balance” – by that the views of maverick scientists that backed the MMR scare story be given equal prominence to the views of mainstream scientists (who represented 99% of the scientific community). The lesson learned by the UK media was that while balance is needed in political reporting, in scientific reporting you need the truth.

Written by Ben Duncan

Podcast: Play in new window | Download